In a recent discussion on The Skiffy and Fanty Show (it’s here), Andrew Liptak, James Decker, Paul Weimer, and I discussed the prevalence of dystopian narratives in science fiction. At one point, Andrew suggested that dystopias are, in large part, responses to the political climate of the author’s present. I agree with this assessment in principle, but I think the idea collapses when applied to works of the popular dystopia tradition — the “dystopia is hip” crowd, if you will. The Iron Heel, however, is the most obvious example of a literary response to a particular political climate — in this case, the U.S. boom-and-bust economy at the turn-of-the-century.*

Told through the memoirs of Avis Everhard, The Iron Heel employs a number of literary devices to explore its political climate. First, London frames Avis’ narrative with Anthony Meredith, a

historian from a future in which the Revolution (i.e., the Socialist Revolution) has succeeded, resulting in an apparent utopia — though we are never given much information about this future world. Meredith introduces and annotates the “journals” of Avis Everhard, herself attempting to relay her past life with Ernest Everhard and the first revolts — all of which fail. We know from the start that both Avis and Ernest are dead, the latter due to some form of execution, but that their desires to see some form of change will find their realization some 700 years later. The confusing narrative structure is probably best understood in terms of time:

- Anthony Meredith is writing from 700 years into the future

- Avis Everhard is writing in the 1930s about events that took place roughly between 1912-1917

- Ernest Everhard’s speeches occur in Avis’ recent past

The Iron Heel not only addresses many of these economic concerns, but it also does so by making their logical steps “forward” a part of the plot of the narrative itself. Instead of imagining a future world where the Oligarchy has taken over, London shows us how the world came to be under the Oligarchy’s control, springing off of a real-world historical/political/economic context that certainly resonated with contemporary audiences. Maurice Goldbloom, writing in Issue 25 of Commentary (1958), argued that the popularity of London and Lewis Sinclair’s (It Happened to Didymus) work stemmed from the fact that “both write recognizably about their own time, and about those aspects of it which are of most concern to ordinary people wherever they are” (454). He further suggested that because many of the issues that presaged the writing of The Iron Heel remained in 1958, London’s novel couldn’t avoid continue relevance throughout history.****

I don’t want to bore everyone with the socialist teachings of the book, themselves a product of London’s attempts to come to terms with his own beliefs about capitalism and socialism.***** Rather, what I want to point out is the way this novel fits into a larger paradigm of political dystopias — that is, works of dystopian literature which are direct responses to real-world concerns, as opposed to the anti-utopians (i.e., the Dystopians) who simply rejected the supposed utopian impulse in political thought. London (and E. M. Forster in the 1909 short story, “The Machine Stops“), like many writers that followed in the wake of the First World War, was one of the first to do just what I am describing, and his work, whether directly or otherwise, influenced dystopian literature through the pre- and post-Second World War periods, from Sinclair Lewis’ fascist dystopia in It Can’t Happen Here (1935) to Yevgeny Zamyatin’s satire of the Soviet Union in We (1921)(not in chronological order, obviously). The trend continued through George Orwell in his most famous works, 1984 (1949; apparently influenced directly by The Iron Heel and We, if Michael Shelden is to be believed in Orwell: The Authorized Biography (1991)) and Animal Farm (1945) — both works deeply concerned with totalitarian forms of government (a common trend); to Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron” (1961) — a dystopian look at radical equality; Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta — totalitarianism again; and P. D. James’ Children of Men — an allegory of reproductive rights.

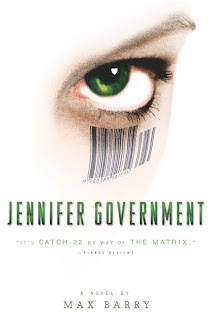

There are plenty of books I’m leaving out, of course, but the idea, I think, is clear. The political format of dystopian literature — the political dystopia — has a long and incredible history in literature, and it is a tradition that continues to this day, such as in Max Barry’s Jennifer Government (2003) or Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale (1999).****** Unlike many works of dystopian literature, the various ones I have mentioned here have directly engaged with real-world issues, often set within the author’s present. They attest to the remarkable ability for dystopia and science fiction to engage with our contemporary world by opening up the dialogue that is so crucial to any political system. Even if we recognize that many of these dystopias are unlikely, the intellectual exercise entailed in reading political dystopias, I believe, fosters the critical faculties we all need to assure the unlikelihood of terrible futures. The Iron Heel, in other words, is not just an important work of literature, but also, and more importantly, a poignant, timeless warning about unchecked economic inequality. More terrifying is the fact that so many of the things London imagines actually happened. A poignant warning indeed….

What do you think about all of this? Feel free to leave a comment.

*I am not properly representing Andrew’s argument here. I recommend checking out the discussion on The Skiffy and Fanty Show.

**This is not to suggest that the U.S. dystopian movement was not significant. It was, but you’ll find a much more concentrated mass of dystopian works in Europe during the aforementioned time period, while the more contemporary moments are dominated by American texts. I could be wrong on this front, though.

***While London imagines the Oligarchy as the end result of monopoly or market capitalism (or boom-and-bust capitalism), the true brunt of the novel, as I see it, is fascism through an incredibly affluent class. The Oligarchy, after all, ceases to be a capitalist government after a while, dominated by what Ernest identifies as the compulsion to expel excess capital (which it refuses to spend on making the lives of individuals better). Thus, the Oligarchy uses its political weight, derived from its original wealth, to create a virtual slave class of laborers and homeless citizens, which it lords over through coercion and violence (if you join the socialist revolution, you will likely die within five years).

****I couldn’t find any reviews from around the publication date of The Iron Heel. I’m sure they exist, but my initial academic searches came up empty.

*****I recommend reading The Iron Heel, though, if only to explore the political depth of London’s work, which are not discussed as often in relation to his more popular novels, White Fang and The Call of the Wild.

******If you have any suggestions for political dystopias originally written in a foreign tongue, feel free to let me know in the comments.

I suppose the "hip-chic dystopian crowd" could otherwise be known simply as post-modern dystopia? Dystopian novels that are merely reactions to the dystopian genre rather than original dystopian novels themselves?

As for political dystopian novels written in non-English languages, i'd suggest either of Kafka's "The Trial" or "The Castle". Then maybe "The First Circle" by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsky, which is not a made-up future but mostly auto-bio yet nevertheless fictional account of Russia during a specific period. The title is a reference to Dante, comparing the world of the novel to the first circle of hell.

I wouldn't call the "hip-chic dystopian crowd" postmodern. Rather, I'd insert the critical utopia and dystopia work of the New Wave period, give or take (60s to 80s, for the most part) into that category. The "hip-chic dystopian crowd" would include things like The Hunger Games or The Maze Runner. Just shitty worlds without any real-world analogue. Not so much responses to dystopia as tours of impossible hells.

Thanks for the suggestions 🙂

The Iron Heel, in other words, is not just an important work of literature, but also, and more importantly, a poignant, timeless warning about unchecked economic inequality.

And I think its relatively far future setting, like 1984's temporal separation from the time of its writing, allows London to make his warnings stand up over time. That's part of the value of science fiction in general, after all.

London's time periods are somewhat different from Orwell's. Orwell was writing in a definite, static time. London wasn't. The story itself is from the perspective of someone writing about events that took place roughly a decade prior, themselves events that would take place merely 4ish years after London wrote the book. The only long-time shift is in the historian's perspective, which is really just a series of annotations and corrections. We never learn anything significant about this future, except than the Revolution succeeds.

So it's somewhat different from Orwell, who sets his work decades ahead. London doesn't really do that, per se.